News Story

Novel Food Sanitation Method Uses Plasma Science to Sterilize Food with the Flip of a Switch

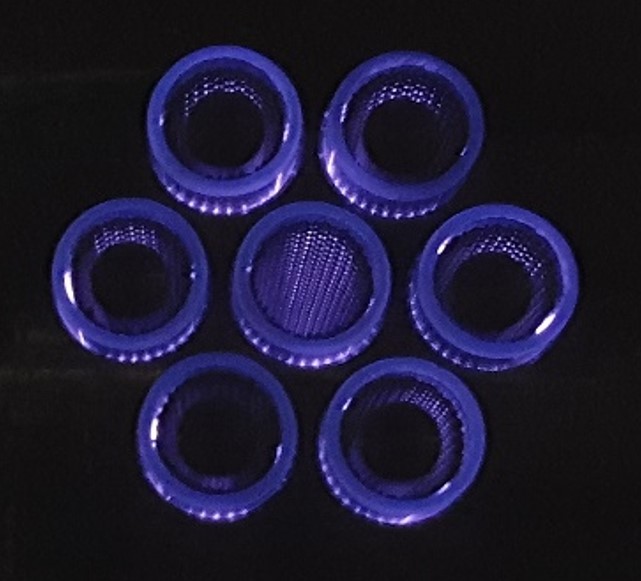

The glow of air plasma generated by Surface Micro-discharge (SMD) reactor, which can be used for bacterial decontamination.

What if you could kill 99% of the potentially harmful bacteria on the surface of your fresh produce in one minute with just the flip of a switch? Consumers could have devices similar in size and operation to a microwave oven, while restaurants and food processors could have larger devices built into their production and processing lines - no water, no waste, no chemical residues, no antimicrobial resistance, and completely sustainable with only a small amount of electricity and air needed. This may sound too good to be true, but it is more plausible than you think thanks to researchers at the University of Maryland (UMD) and their work in low-temperature plasma science.

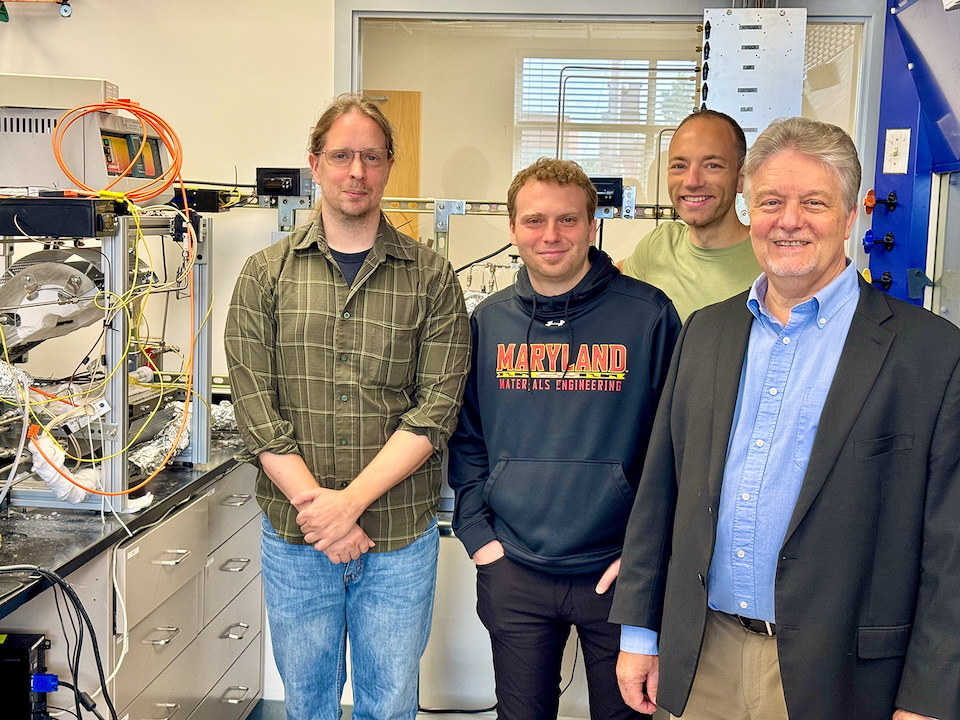

In a paper recently published in Plasma Processes and Polymers, researchers from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering (MSE), the Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics (IREAP) and Nutrition & Food Science in the College of Agriculture & Natural Resources reported 99% E.coli kill on the surface of fresh produce after just one minute of treatment in a process called etching - where the tiniest layer of the outer membrane of bacteria is etched away, or removed, to kill surface bacteria using what is essentially electrified air, also called plasma.

“Plasma is what’s called the fourth state of matter, and it is technically the most abundant state of matter in the universe,” said MSE Professor, Gottlieb Oehrlein. “There are the solid, liquid, gaseous, and the plasma states of matter. The latter is an electrified gas and the most energetic and reactive state of matter. We can use electrical energy to produce this state from air, and the reactive species generated have very strong impacts on pathogens where they can etch part of their outer membranes and change them biochemically.”

Oehrlein and his team are known in the field of plasma science for their work on plasma-material interactions. Most people think of plasma as the technology behind plasma televisions, but this electrified air can be used in many other ways. In fact, it is already prominently used in the healthcare industry to sanitize surgical tools, and is specifically used in dermatology for the treatment of skin diseases and cancers. The plasma is concentrated to look like a very tiny blowtorch.

“Microscopically it is close to a blowtorch, but it is a combination of material removal called etching and surface modification, changing the chemical bonds on the surface,” said Pingshan Luan, MSE post-doc and first author on the study. “Once the composition is changed, the bacteria has no functional or structural integrity.”

This is what makes the concept of antimicrobial resistance irrelevant in a process like this, because the changes are structural, making this a very appealing option for food sanitation.

“Resistance would never happen with plasma because this is structural stress and breakdown,”, said Oehrlein. It is also a cold process unlike a traditional blowtorch, which is perfect to protect food quality. “Right now, there is an explosion of interest in plasma sterilization for food, and this work provides some mechanistic understanding on processes that are operative,” Oehrlein added.

This is in part due to the recent rise in foodborne illness outbreaks and the increased attention to food safety. People are making healthier food choices, driving higher demand for fresh and unprocessed food. Fresh fruits and vegetables are often consumed raw, contributing to increases in foodborne disease outbreaks from 0.70% in the 1970s to 33% in 2012. While foodborne illness from fresh produce is rare, the need to ensure that these products are properly sanitized before consumption is apparent.

“The U.S. has the one of the safest food supply, but fresh produce is still a substantial source of outbreaks,” said Rohan Tikekar, Professor of Nutrition & Food Science. “The problem is that we don’t have a kill step for our fresh produce. We harvest them, we might do some postharvest cooling, then we may wash the produce to pack it and ship it.”

However, even washing produce can be problematic. “The washing process is a double-edged sword,” says Tikekar. “It makes produce look appealing and removes dirt, but if it is not done properly, water becomes a carrier for this small amount of bacteria to spread to a larger batch of produce. You may start out with say 10 lettuce heads that are contaminated, and with improper washing, you might end up with 10 tons of lettuce that is contaminated.”

On top of that, this process is highly resource intensive and not particularly environmentally friendly. “Washing of produce is an energy and resource-intensive operation, and while the numbers vary, you could use as much as 10 pounds of water per pound of produce,” says Tikekar. “This can be a major source of water consumption. In addition, typically you have to chill the water to maintain the quality of the produce, so the whole process is a refrigerated process which takes a lot of energy. What we have been doing is adding chlorine-based sanitizers to the water, and this way the bacteria gets killed before it gets transferred to another product. This is highly effective, but chlorine-based sanitizers also dissipate quickly, and you have to replenish these continuously changing chlorine levels. While this is safe and effective, there are limitations to this process, and there is a push to find alternative methods to compete with chlorine as a food sanitizer due to perceptions and issues of resistance.”

“Conventional decontamination processes use a lot of water and chemical processes like chlorine, and this is a huge water bill, and eventually consumers pay that bill,” explains Luan. “The plasma approach doesn’t use any water. Pretty much all we need is a little electricity and air. Air is pretty much free at this point, and electricity is only about 12 cents per kilowatt hour, and with our technology, you could run it for the whole day and it wouldn’t cost a single dollar. The process is environmentally friendly, cheap, uses no water, and can be integrated easily into existing food processing lines onto conveyor belts or scaled in many ways.”

According to Oehrlein, it could be as easy as flipping a light switch on and off. “You could do this at an industrial scale but you can also imagine doing it at a restaurant scale, dining halls, or even individual consumers’ levels where you can potentially have a microwave-like device that could inactivate pathogens just prior to consumption,” says Tikekar.

While there is little risk associated with this process, researchers are prepared to dig into this in the future.

“Side effects of the processing technology are still being examined, so in the future we will look more closely at nutritional content,” says Luan. “The only thing so far tested is the physical appearance of the food, but nutrients like vitamins and antioxidants haven’t been characterized. However, from our experience, plasma processing technology is a surface processing technology, so the affected volume is usually within a couple tens of nanometers from the surface, so very small. Most of the nutrient is on the inside of the food, so it is unlikely that nutritional content is affected. It is also a simple oxidation process, so there is no logical health concern, but we are still looking into these and need to understand all potential side effects before this technology can be used. The potential is there and very promising.”

For additional information:

Luan, P., Bastarrachea, L.J., Gilbert, A.R., Tikekar, R., Oehrlein, G.S. Decontamination of raw produce by surface microdischarge and the evaluation of its damage to cellular components, 2019. DOI: 10.1002/ppap.201800193.

Published April 17, 2019